You & Polyester: Getting Along, Swimmingly

700,000

Each polyester garment can release up to 700,000 fibers per revolution of a washing machine’s drum.

78 million tons

80% used in textiles. It represents about 80% of all synthetic fiber production, driven by its low cost, durability, and popularity in fast fashion

Polyester is the dominant fiber in the textile industry, accounting for approximately 57% to 59% of total global fiber production as of 2023-2024. It makes up over half of all fibers used in apparel and textiles, driven by its affordability and versatility. Nearly 90% of this production is fossil-based.

Polyester fabric is lightweight, wrinkle-resistant, quick-drying, and moisture-wicking, making it ideal for activewear, home textiles, and custom (print-on-demand) apparel.

It’s also incredibly damaging to the enivironment. Producing nearly 60% of all textiles globally from carbon-dense fossil fuels poses some very serious problems:

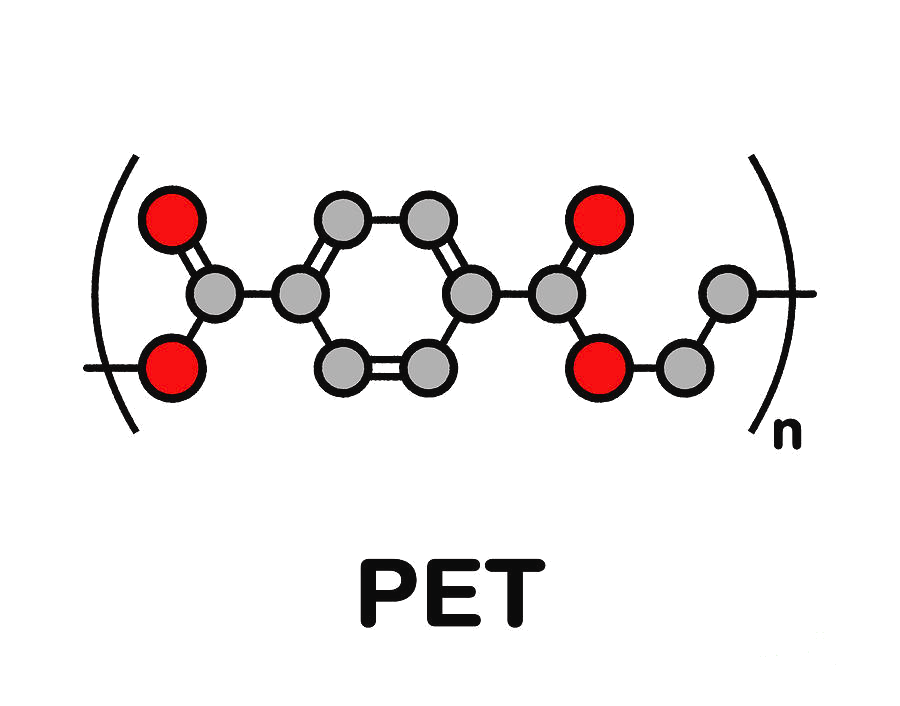

Polyester types include PET, PCDT, microfiber, recycled polyester (rPET), and emerging plant-based polyester fibers.

Recycled polyester helps reduce reliance on fossil fuels, but it still contributes to microplastic pollution during washing.

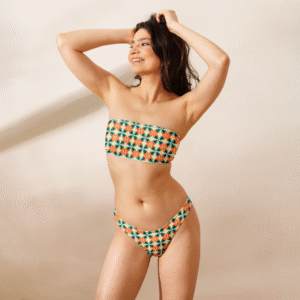

With the above in mind, we’ve searched for swimwear for women and men that uses the highest percentage of recycled polyester. We looked for durability, quality and particularly, density of the fabric.

We also made sure that the recycled polyester was, indeed, recycled in accordance with best practices.

These are the best matches we found. Each is uniquely manfactured for you and features our bold, modern designs that will make you shine while while showing off your commitment to the environment.

-

Henri Matisse: The Sheaf (1953) Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$46.00 -

Alight Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$46.00 -

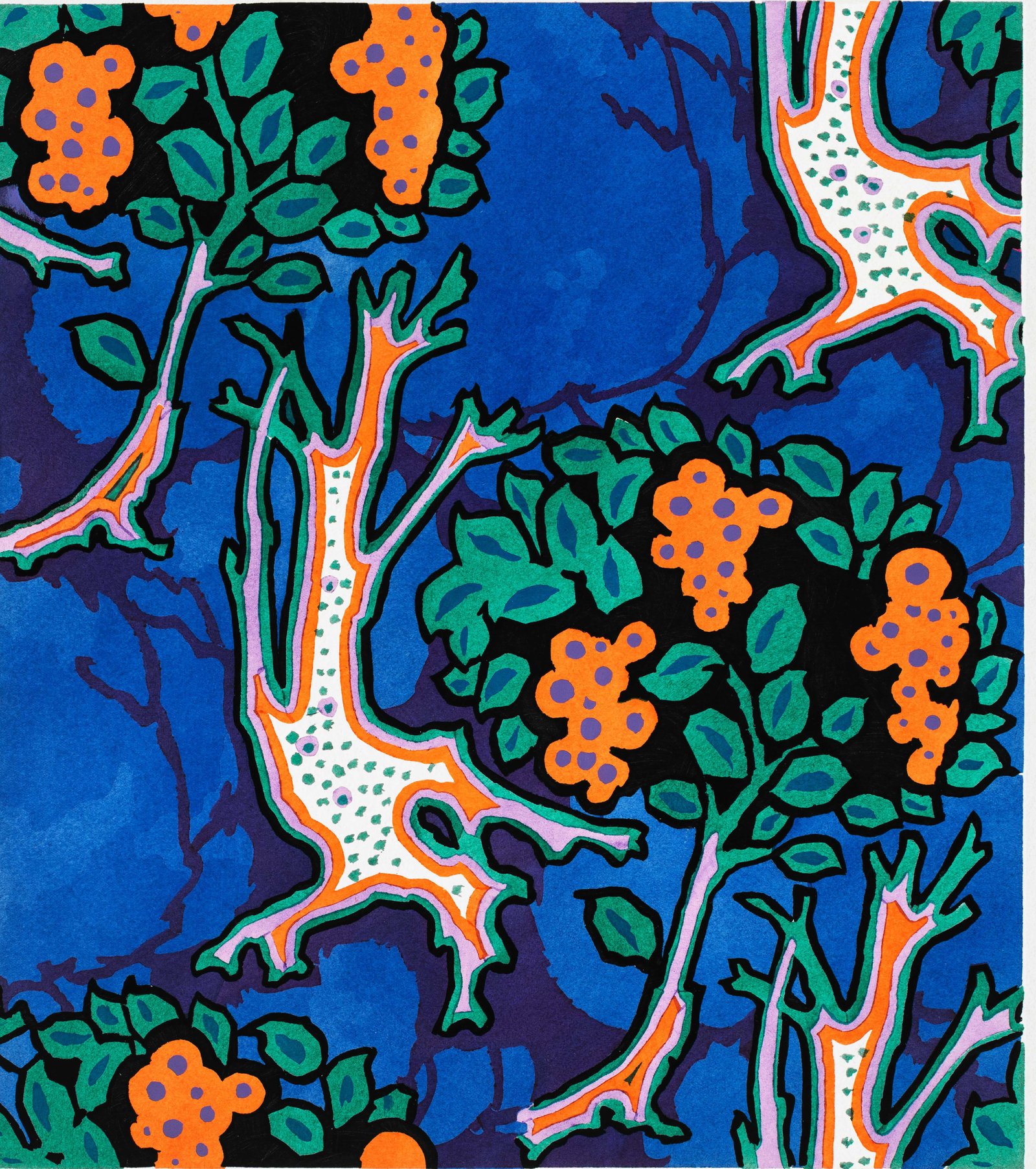

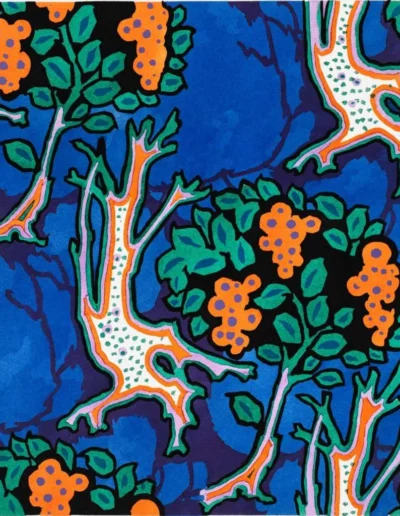

Chinoiserie Floral Print Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$46.00 -

Paul Klee-Inspired Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00 -

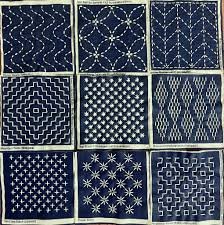

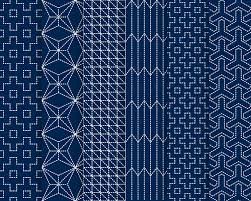

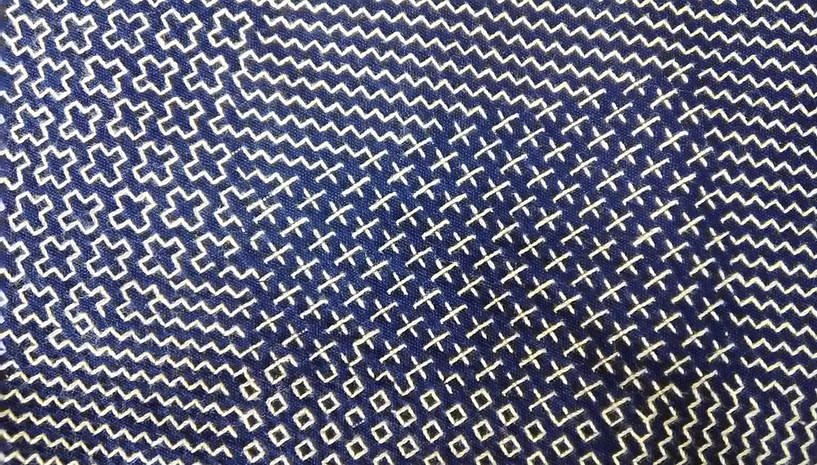

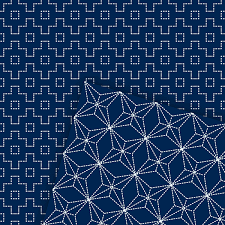

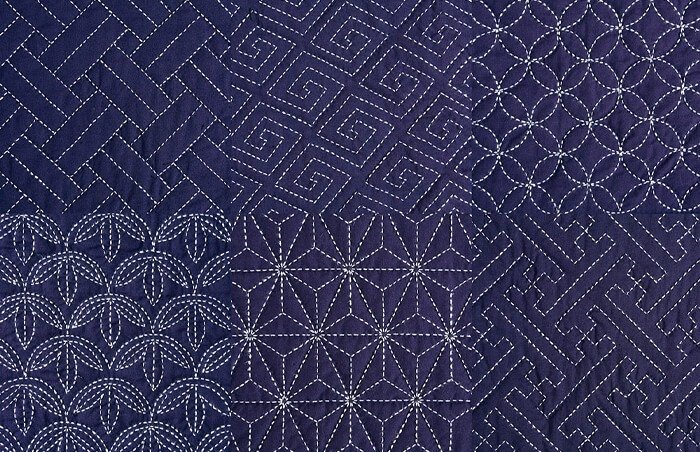

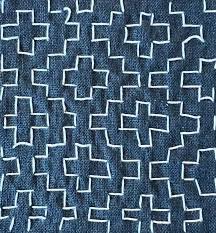

Complex Sashiko Pattern Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00 -

Split Quad Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00

Women's

-

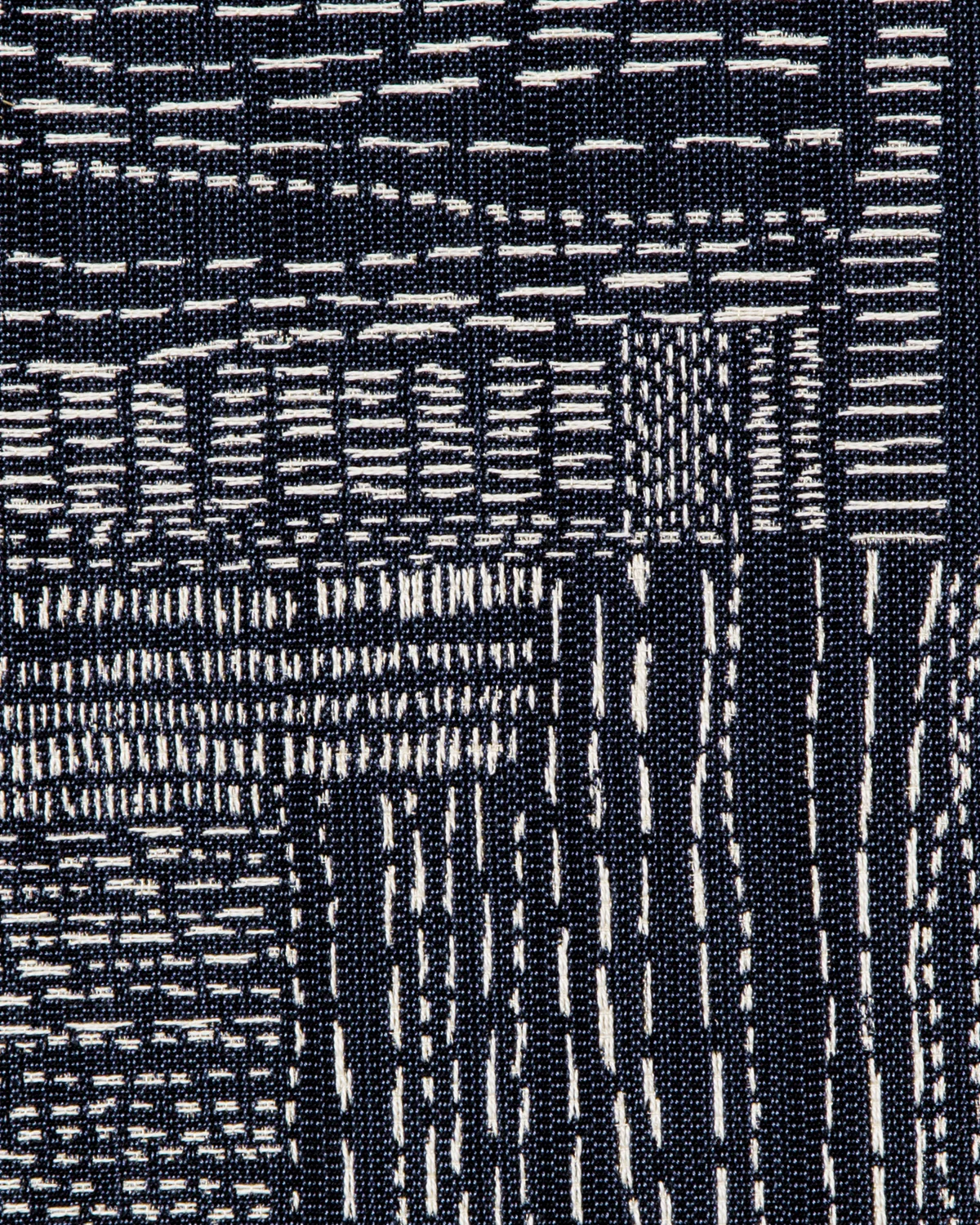

Curved Sashiko Pattern Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00 -

Astra Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00 -

Prism Plank One-Piece Swimsuit

Price range: $35.00 through $42.00 -

Tropekal One-Piece Swimsuit

Price range: $44.00 through $50.50 -

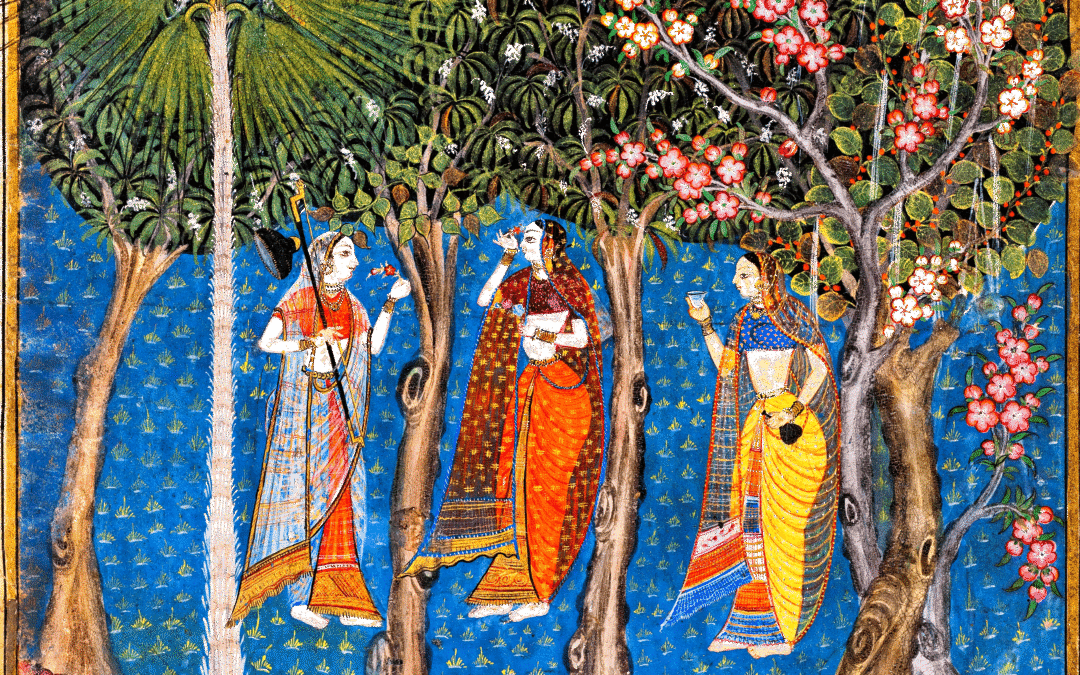

Kano One-Piece Swimsuit

Price range: $44.00 through $50.50 -

Jolie Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$42.00 -

Tasiz Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$42.00 -

Emblem Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$42.00 -

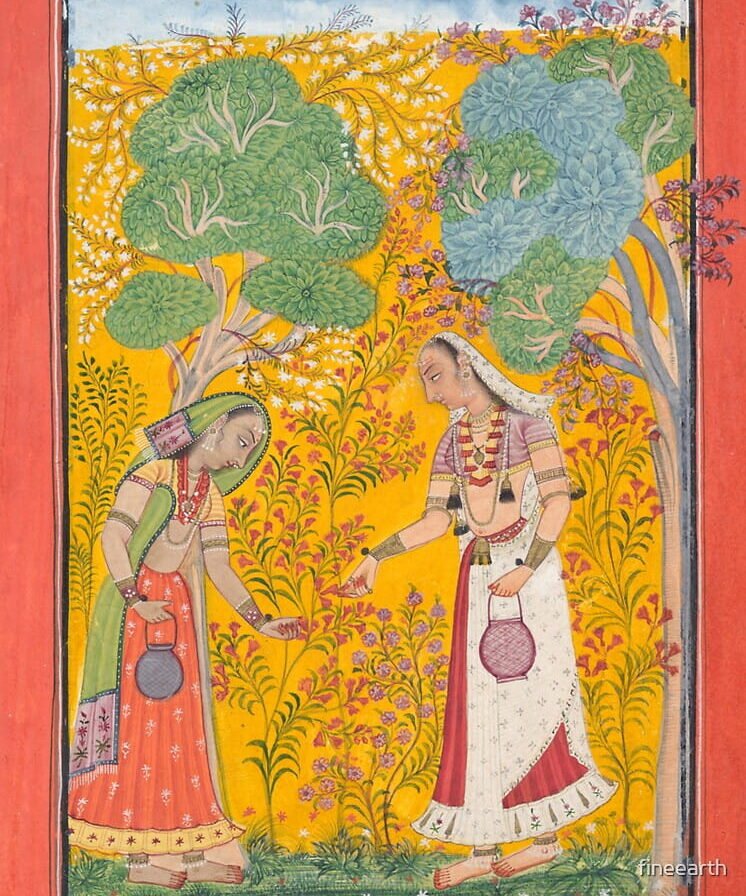

Arabe Deux Recycled Bandeau Bikini

$42.00 -

Atsui Recycled High-Waisted Bikini

$49.00 -

Blue Line One-Piece Swimsuit

$39.00 -

Paisley Mandala Recycled String Bikini

$39.00 -

Paisley Mandala Recycled String Bikini Top

$27.00 -

Soft Frequency Recycled High-Waisted Bikini

Price range: $49.00 through $54.00 -

Soft Frequency One-Piece Swimsuit

$49.00 -

Pistil One-Piece Swimsuit

$49.00

Recycled polyester (rPET), which is made from post-consumer plastic bottles and textile waste, is one of the promising solutions for the swimwear industry. Its use drastically reduces the environmental impact of conventional polyester, which is typically derived from petroleum. It is highly durable and resistant to chlorine, saltwater, and UV rays.

Men's

-

Tourney Men’s Swim Shorts

$44.00 -

Saragasso Men’s Swim Shorts

$44.00 -

Blue Tile Men’s Board Shorts

$31.00 -

Corfu Men’s Swim Trunks

$49.00 -

Be at Peace Swim Trunks

$42.00 -

Split Blue Swim Trunks

$39.00 -

Blurry Tides Swim Trunks

$39.00 -

Matte Algae Swim Trunks

$39.00 -

Triangulated Men’s Swim Trunks

$55.00 -

Geo Men’s Swim Trunks

$55.00 -

Spectrum Men’s Swim Trunks

$55.00