No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Konan Tanigami, a prominent Nihon-ga artist from 1879 to 1928, is celebrated for his exceptional contributions to the Kacho-e genre, which focuses on the intricate depiction of birds and flowers. Notably, he distinguished himself as the first Japanese artist to incorporate Western flowers into his work, bridging the gap between traditional Japanese aesthetics and Western botanical subjects. His innovative approach not only enriched the Kacho-e tradition but also opened new avenues for artistic expression in Japan.

Tanigami Konan, born in 1879 in the historical city of Nagoya, Japan, grew up surrounded by the rich cultural tapestry that defined the Meiji era. He was drawn to art from a young age, enrolling in the Kyoto School of Arts where he honed his skills in traditional Nihon-ga techniques. Under the guidance of renowned mentors, Konan developed a keen eye for detail, allowing him to bring a sense of vibrancy to his subjects.

Konan’s artistic journey flourished as he became recognized for his innovative approach to Kacho-e, a genre focused on birds and flowers. His career spanned several decades, during which he not only exhibited widely but also became the first Japanese artist to dive into the world of Western flowers. This daring endeavor, along with his participation in international exhibitions, let the world know that Japanese art was not a solitary island but a bridge connecting diverse natural beauty across oceans.

Kacho-e is basically the beautiful lovechild of birds and flowers, taking center stage in the Nihon-ga (Japanese painting) scene. Characterized by delicate brushwork and a focus on natural beauty, Kacho-e pieces often highlight seasonal blooms and graceful wildlife. Imagine a serene setting, where a sparrow is perched on a cherry blossom branch—poetry in visual form. The detail is so fine, it’s like the artist had a mini microscope while painting!

Emerging during the Edo period, Kacho-e became a stylish staple for art lovers, reflecting the shifting interests of Japanese society. Capitalizing on the West’s fascination with Japanese culture, Kacho-e blossomed in popularity, often embodying a meditative relationship between nature and humanity. So, while Konan painted Western flowers, he was also part of a long tradition that appreciated the beauty of nature—albeit with a modern twist.

Konan’s reputation as a daring innovator is well-earned, especially when it comes to his approach to Western flowers. He didn’t just dip his toes into unfamiliar waters; he cannonballed right in! Blending the intricate techniques of Nihon-ga with vibrant blooms like roses and daisies, he created an exciting fusion that made flower arrangements feel fresh and new. His work often had viewers wondering, “Is that a bouquet from my garden or the pages of a Western floral catalog?”

While many of his contemporaries timidly stuck to traditional Japanese flora, Konan boldly ventured into the uncharted territory of Western botanicals. Artists like Takehisa Yumeji were also experimenting, but none quite captured the same flair for floral diversity as Konan. His ability to intermingle Western aesthetics with Eastern sensibility set him apart, making him a trendsetter in a field that was still finding its footing in a rapidly changing artistic landscape.

If there’s one thing that defines Konan’s art, it’s his deep connection with nature. Every brushstroke seemed to whisper an ode to the delicate balance of flora and fauna. With a penchant for detail, his pieces captured not just the visual appeal but also the essence of the natural world. Whether it was the play of light on petals or the rustle of leaves, Konan’s paintings felt alive, as if nature was right there in the room with you.

The early 20th century was a melting pot of artistic movements, and Konan wasn’t immune to their influence. The Impressionists, with their focus on light and color, left a mark on him, perhaps inspiring his vivid interpretations of Western flowers. Additionally, the Arts and Crafts movement’s emphasis on nature and craftsmanship resonated with his artistic philosophy. This cross-pollination of ideas allowed Konan to create artwork that was a harmonious blend of Eastern and Western aesthetics, proving that art truly knows no boundaries.

Tanigami Konan’s portfolio features an impressive array of paintings that boast a harmonious blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and Western botanical influences. His work, such as “Peonies and Birds,” exemplifies this unique fusion, showcasing not just the beauty of the depicted flowers but also a meticulous attention to detail that invites viewers to appreciate the harmony of nature. Konan’s ability to illustrate Western blooms with the grace typical of Kacho-e art not only expanded the thematic repertoire of Nihon-ga but also sparked conversations about Japan’s engagement with globalization in the early 20th century.

Konan wasn’t just a pretty face in the art world; he was a trailblazer. His innovative use of color and texture reflected his keen observation of natural forms, elevating the Kacho-e genre. Embracing techniques such as layering and the incorporation of new pigments from Western sources, he created works that were more vivid and lifelike than ever before. This innovation didn’t just set a new standard; it redefined how Japanese artists approached floral and avian subjects, ushering in a fresh era of aesthetic exploration.

The ripples of Konan’s artistic contributions can be felt even today. Many contemporary artists cite him as an inspiration for their own explorations of nature and the interplay between Eastern and Western art techniques. His fearless approach encourages new generations to experiment with their styles, bridging traditional forms with modern expressions, and invites a re-examination of cultural identity through art.

Today, Konan’s works are more than just beautiful images; they are treasured artifacts representing the evolution of Japanese art. Museums and galleries around the globe recognize his contributions, often featuring his works in exhibitions that highlight the dialogue between East and West. Art enthusiasts and scholars alike are increasingly dedicated to preserving his legacy, ensuring that the vibrant colors and intricate details of Konan’s flora will continue to flourish for future generations.

During his lifetime, Tanigami Konan’s works were showcased in several high-profile exhibitions, drawing significant attention and acclaim. His participation in the 1910 Japan-British Exhibition introduced Western audiences to his unique vision and helped establish his reputation as a leading Kacho-e artist. These exhibitions paved the way for broader appreciation of Japanese art, allowing Konan to stand confidently in the spotlight of an evolving art scene.

Even after his passing in 1928, Konan’s art has continued to gain recognition. Various art institutions have posthumously honored his work through exhibitions and special collections that celebrate his contributions to the Nihon-ga movement. Additionally, awards recognizing his influence on the Kacho-e genre further cement his status as a pivotal figure in the history of Japanese art.

Joan Miró Ferra was born April 20, 1893, in Barcelona. At the age of 14, he went to business school in Barcelona and also attended La Lonja’s Escuela Superior de Artes Industriales y Bellas Artes in the same city. Upon completing three years of art studies, he took a position as a clerk. After suffering a nervous breakdown, he abandoned business and resumed his art studies, attending Francesco Galí’s Escola d’Art in Barcelona from 1912 to 1915. Miró received early encouragement from the dealer José Dalmau, who gave him his first solo show at his gallery in Barcelona in 1918. In 1917 he met Francis Picabia.

Miró’s spirited depiction of The Tilled Field also has political content. The three flags—French, Catalan, and Spanish—refer to Catalonia’s attempts to secede from the central Spanish government. Primo de Rivera, who assumed Spain’s dictatorship in 1923, instituted strict measures, such as banning the Catalan language and flag, to repress Catalan separatism. By depicting the Catalan and French flags together, across the border post from the Spanish flag, Miró announced his allegiance to the Catalan cause.

Hungarian, 1895 – 1946

He also worked collaboratively with other artists, including his first wife Lucia Moholy, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Herbert Bayer.

His largest accomplishment may be the School of Design in Chicago, which survives today as part of the Illinois Institute of Technology, which art historian Elizabeth Siegel called “his overarching work of art”. He also wrote books and articles advocating a utopian type of high modernism.

Carbon offsetting is a way to compensate for the carbon dioxide we spew into the atmosphere by funding projects that reduce greenhouse gases or absorb carbon from the air. At cgk.ink, this means investing in renewable energy sources, reforestation efforts, and energy-efficient technologies that help balance out the environmental impact of shipping and packaging.

Stripe Climate is the easiest way to help promising permanent carbon removal technologies launch and scale. cgk.ink has joined a growing group of ambitious businesses that are changing the course of carbon removal.

Carbon Balance Pte. Ltd. is a sustainability platform based in Singapore providing a calculator API to measure the GHG footprint of ecommerce transactions and an Integration Plugin for popular ecommerce enablers such as WooCommerce, EasyStore, Shopify with flexible options to offset footprint by contributing to trustworthy projects.

These pieces of software complement our other intiatives, such as:

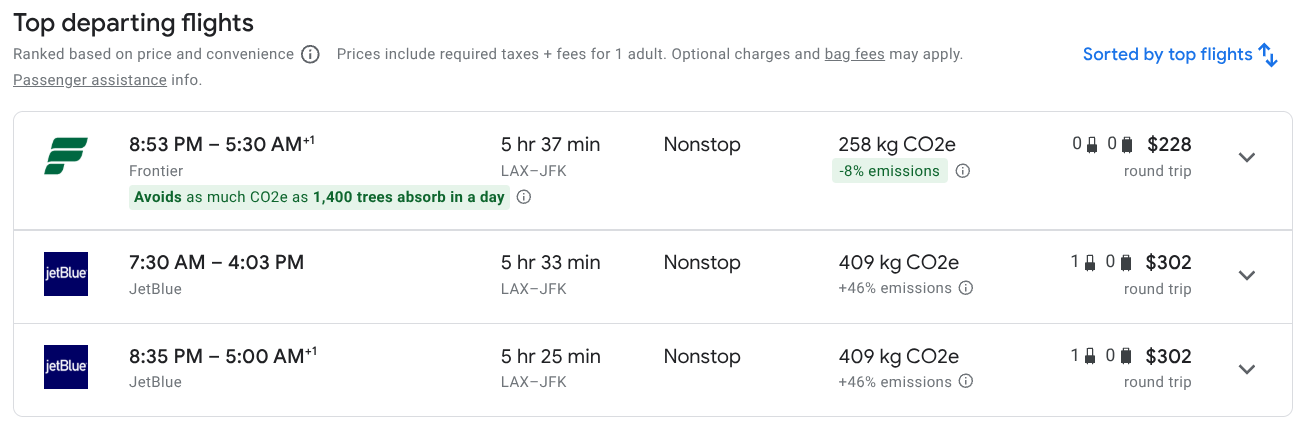

Google Travel, as well as other travel and hotel search sites, have formulated a way to compare carbon emission variations among similar routes. The impetus is on both the airline and the consumer to choose among the available options with ecological criteria being included.

Showing 85–96 of 96 resultsSorted by latest

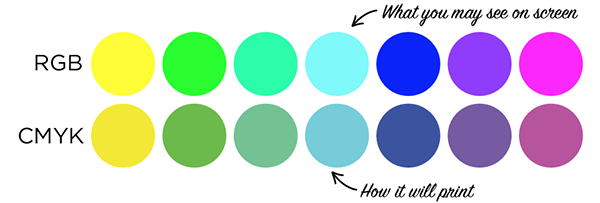

Color is one of the most essential design elements. This site uses many different techniques to deliver items that are as sharp and vivid as the images that are presented on the web site.

There are very specific differences between what is displayed versus what is printed. Let’s take a quick look at some basic physics of rendering colors:

RGB is an additive color model, while CMYK is subtractive.

RGB uses white as a combination of all primary colors and black as the absence of light. CMYK, on the other hand, uses white as the natural color of the print background and black as a combination of colored inks. Graphic designers and print providers use the RGB color model for any type of media that transmits light, such as computer screens. RGB is ideal for digital media designs because these mediums emit color as red, green, or blue light.

RGB is best for websites and digital communications, while CMYK is better for print materials. Most design fields recognize RGB as the primary colors, while CMYK is a subtractive model of color.

With the RGB color model, pixels on a digital monitor are – if viewed with a magnifying glass – all one of three colors: red, green, or blue. The white light emitted through the screen blends the three colors on the eye’s retina to create a wide range of other perceived colors. With RGB, the more color beams the device emits, the closer the color gets to white. Not emitting any beams, however, leads to the color black.

This is the opposite of how CMYK works.

CMYK is best for print materials because print mediums use colored inks for messaging. CMYK subtracts colors from natural white light and turns them into pigments or dyes. Printers then put these pigments onto paper in tiny cyan, magenta, yellow, and black dots – spread out or close together to create the desired colors. With CYMK, the more colored ink placed on a page, the closer the color gets to black. Subtracting cyan, magenta, yellow, and black inks create white – or the original color of the paper or background. RGB color values range from 0 to 255, while CMYK ranges from 0-100%.

Source: Boingo Graphics