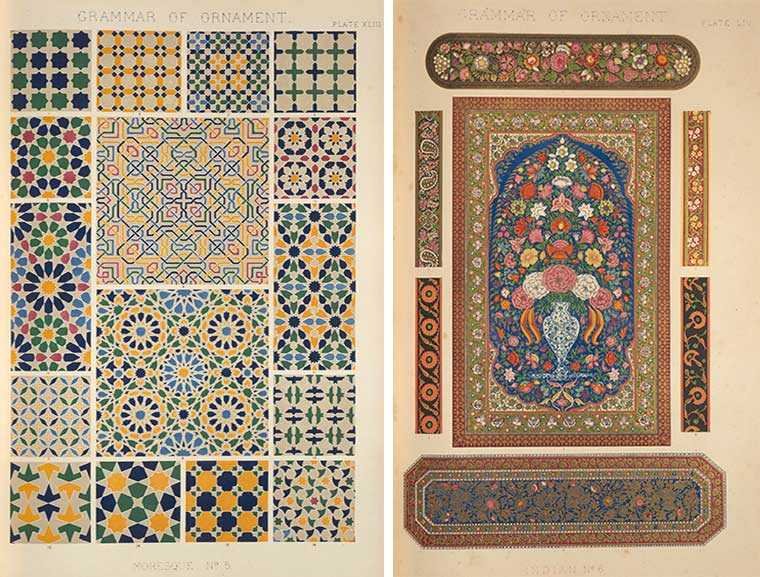

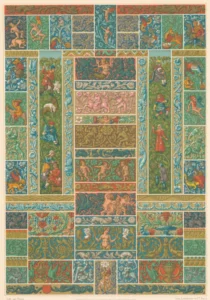

The Grammar of Ornament

—Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament

While we may often note that current society is changing at a breakneck speed, we do have to take note that this has happened before. Arguably, the 19th Century beats us at our own game on the fundamental-change level.

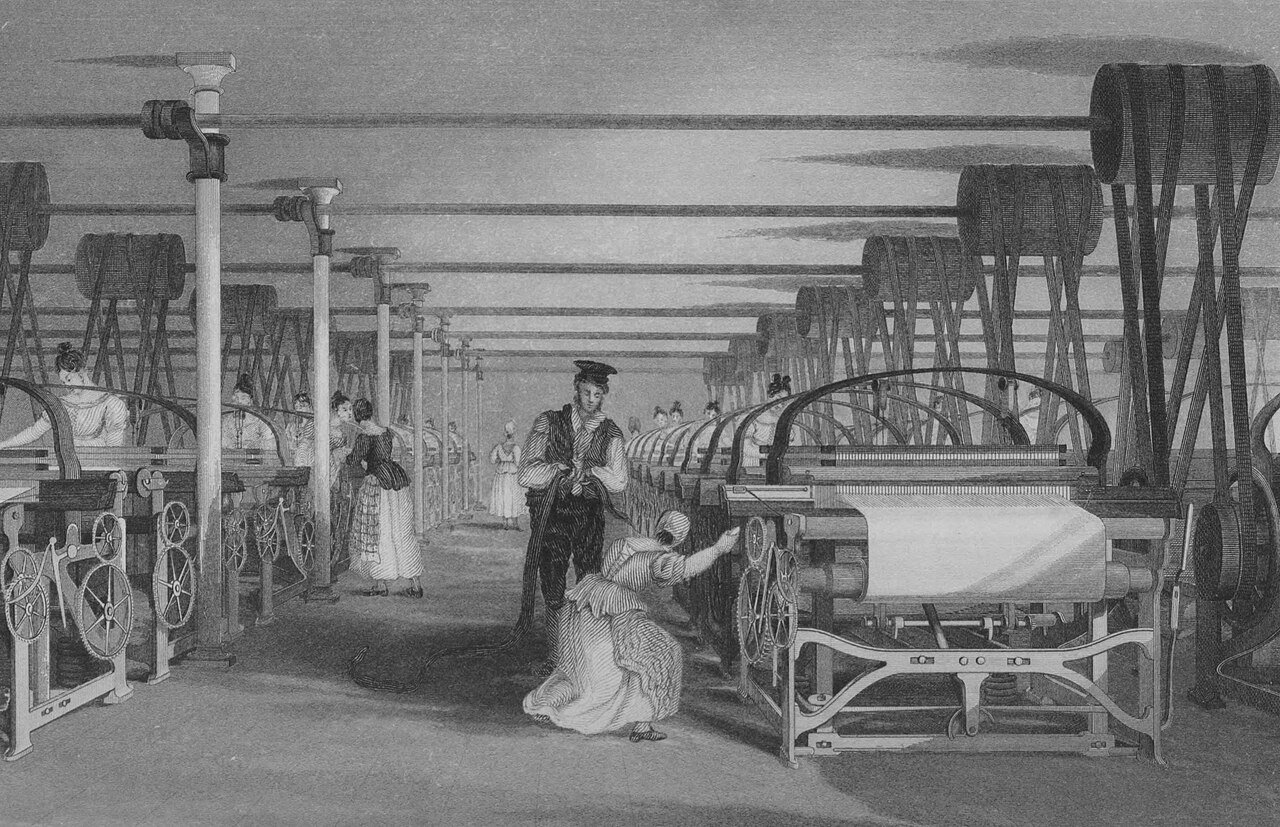

The 19th century was an era of rapidly accelerating scientific discovery and invention, with significant developments in the fields of mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, electricity, and metallurgy that laid the groundwork for the technological advances of the 20th century. The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain and spread to continental Europe, North America, and Japan. The Victorian era was notorious for the employment of young children in factories and mines, as well as strict social norms regarding modesty and gender roles.

The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolished in much of Europe and the Americas. The First Industrial Revolution, though it began in the late 18th century, expanding beyond its British homeland for the first time during this century, particularly remaking the economies and societies of the Low Countries, the Rhineland, Northern Italy, and the Northeastern United States. A few decades later, the Second Industrial Revolution led to ever more massive urbanization and much higher levels of productivity, profit, and prosperity, a pattern that continued into the 20th century.

The first electronics appeared in the 19th century, with the introduction of the electric relay in 1835, the telegraph and its Morse code protocol in 1837, the first telephone call in 1876,[2] and the first functional light bulb in 1878.[3] Society rapidly urbanized, bringing populations increasingly together into smaller spaces. The first notes of globalization brought influences from around the world to the same table, with varying results. From a Western perspective, the new cultures were ripe to be harvested. The Eastern-perspective, it presented new threats and cultural influence without precedent. The world, in fact, was becoming smaller.

The increasingly urbanization of Europe and the United States brought about new challenges to traditional aesthetics and behaviors. How does one distinguish oneself from a sea of common faces? What importance does a dwelling have and how does it become a home? An ever-evolving social hierarchy demanded that new styles, techniques and designs be invented — and quickly.

the Emergence of Decorative Arts

dec·o·ra·tive arts

/ˌdek(ə)rədiv ˈärts,ˌdekəˌrādiv ˈärts/

noun

plural noun: decorative arts; noun: decorative art

the arts concerned with the production of high-quality objects that are both useful and beautiful.

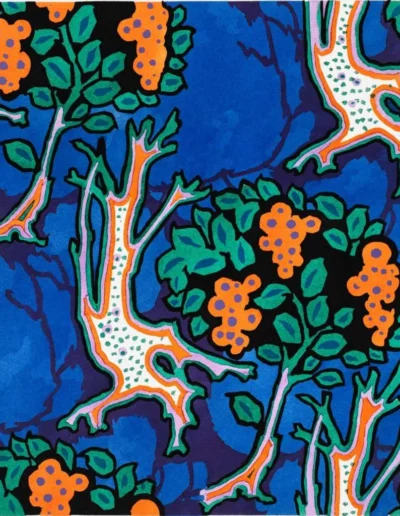

Ceramics, glassware, basketry, jewelry, metalware, furniture, textiles, clothing, and other such goods are the objects most commonly associated with the decorative arts. Many decorative arts, such as basketry or pottery, are also commonly considered to be craft, but the definitions of both terms are arbitrary.

The term “decorative arts” is not meant to be derogative. It was popular in the 70s to dismiss this as a “lesser” art and thankfully, we’ve decided collectively to rather group all functional art under the term “design.” The artists we discuss in our Fine Arts Collection are very much masters of fine art as well as exquisite craftspeople. I argue that decorative arts are actually more democratic and open to including fine art in our everyday life.

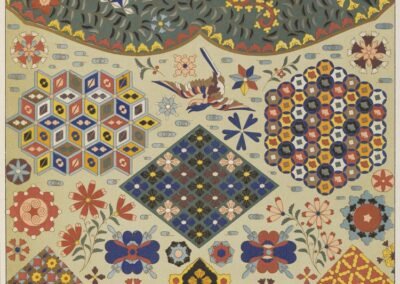

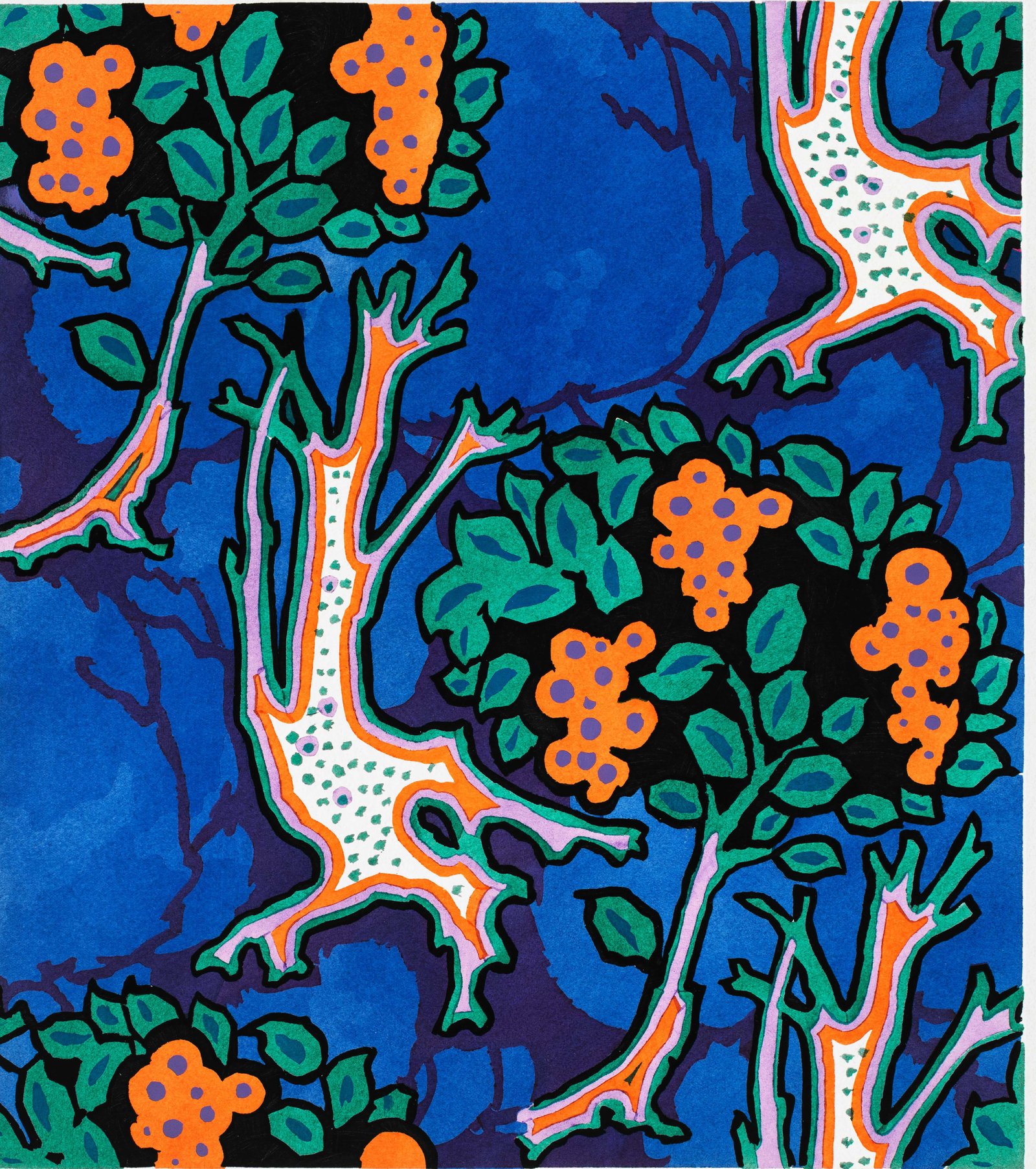

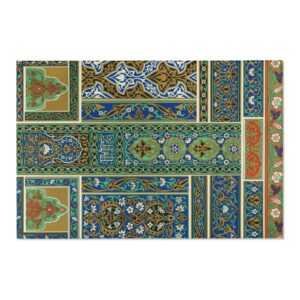

And then there’s “retro.” We constantly revisit previous eras to gain inspiration for our own, modern times. Likewise, The Victorian era is known for its interpretation and eclectic revival of historic styles mixed with the introduction of Asian and Middle Eastern influences in furniture, fittings, and interior decoration. The Arts and Crafts movement, the aesthetic movement, Anglo-Japanese style, and Art Nouveau style have their beginnings in the late Victorian era and gothic period.

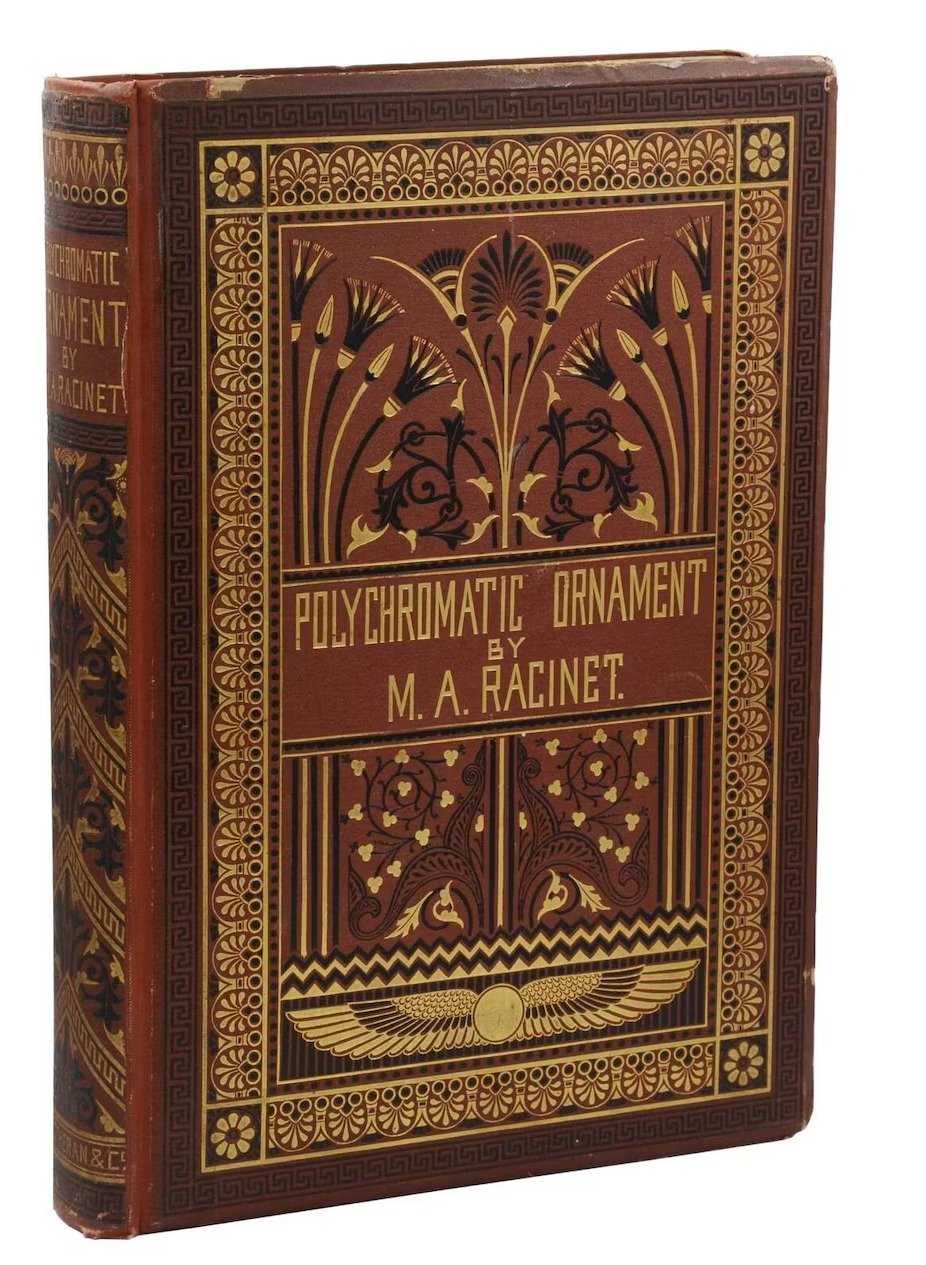

I’m specifically interested in a handful of artists who made a thoughtful, meaningful jump to bring arts to bear weight on everyday existence. We’ve talked about Racinet. And Morris. There are several dozen others including, Tiffany, Lalique, Tamara de Lempicka, Erté (a great article re: “the top 10” is here, click on it!) are among the most notable.

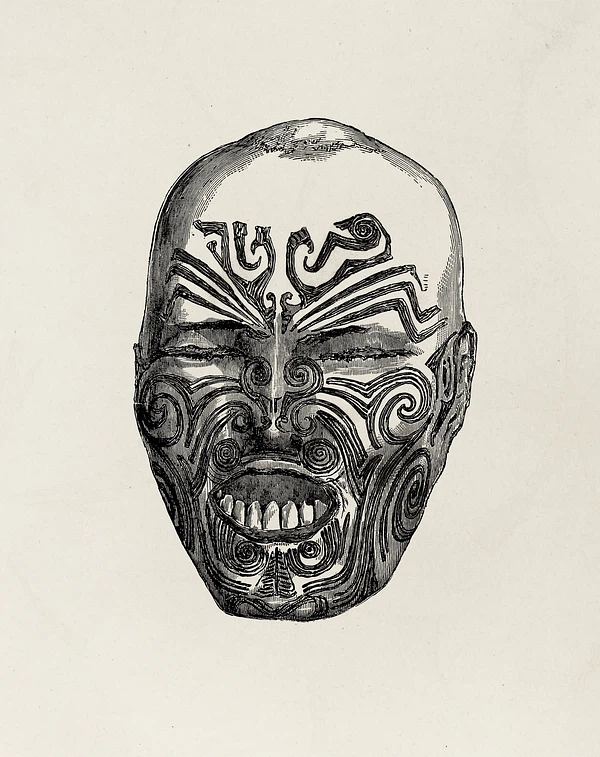

Owen Jones

In the opening chapter to his seminal work The Grammar of Ornament, Owen Jones stresses the fact that one of the universal qualities among humankind is the desire to make beautiful things. To illustrate this point, he uses the somewhat macabre example of a severed preserved head of a Maori warrior (mokomokai), then thought to be a woman, which was covered in an elegant pattern of facial tattoos. He admired it particularly for the harmonious way in which the responsible artist had married the tattooed lines with the natural shapes of the human face. Rather than concluding that ornament belongs purely to the primitive, as others would argue later, Jones realized through his confrontation with this ethnological specimen that the Maori possessed an innate understanding of beauty that was alien to modern Western society.

While Jones’s ideas slowly took root in art education over the following decades, which in turn influenced the development of new artistic movements such as Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau, The Grammar of Ornament did not bring about a direct change in artistic practice. In fact, as Jones himself anticipated, we often find patterns and motifs from the book copied and applied to objects and interiors dating from the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

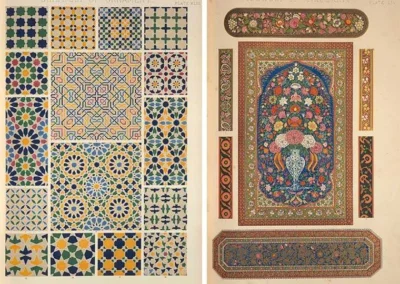

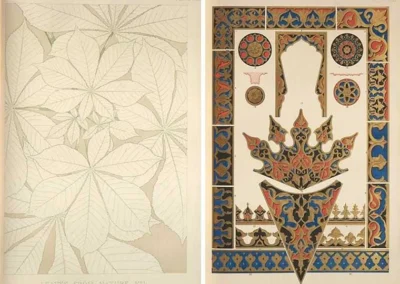

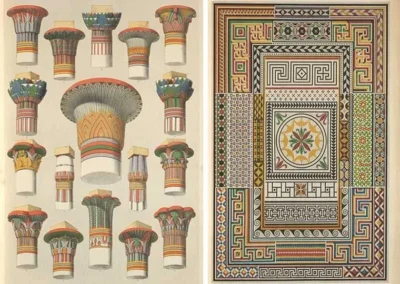

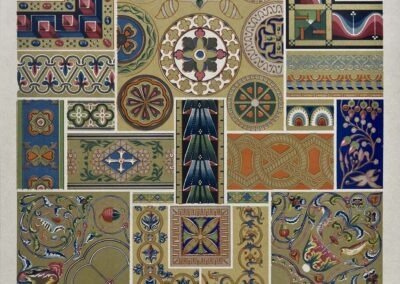

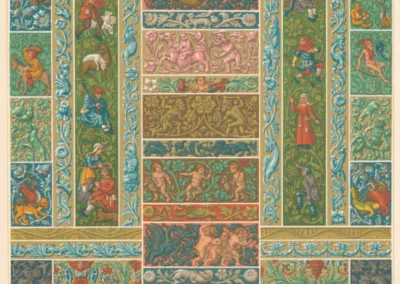

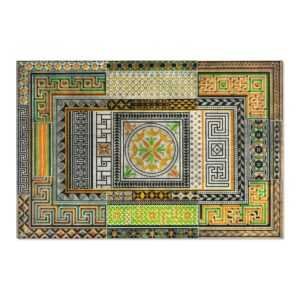

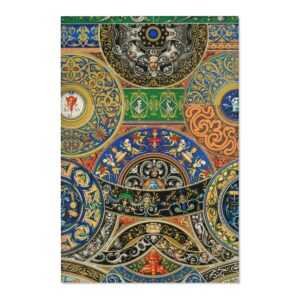

The Grammar was celebrated first and foremost for its outstanding folio-sized color lithographs, which represented the latest and most sophisticated innovations in the field of printmaking. Color lithography had been in use for several decades, but because each color was printed from a separate lithographic stone, most commercial publications were printed in a limited palette of three or four colors. Since color played a crucial role in Jones’s work, he took charge of the production himself and employed assistants to work out the patterns on lithographic stones, with certain plates requiring as many as twenty distinct stones. The high quality of Jones’s color plates quickly turned the luxurious first edition of the book into a collector’s item. Their appeal greatly outlasted Jones’s intellectual arguments, which were omitted altogether in the various posthumous editions, and facsimile reproductions published in the later nineteenth and twentieth century.

As a writer, I have to include at least one reference to literature when discussing art, fine or otherwise.

While he is now seen as the epitome of wit and sophistication, Oscar Wilde was prosecuted and was killed under the same Victorian culture that produced the mentioned artwork.

It is important to note that his trial (3 April 1895) indeed changed the very vocabulary he wrote in: English. Before his trial, there were homosexual acts, however one could not be homosexual. It was not a noun. It was unthinkable to call someone a “homosexual.” Certainly a “sodomite” but that’s a different word altogether. Your identity was not in question, your acts were. That changed from an adjective to a noun due to his trial.

In 2017, Wilde was among an estimated 50,000 men who were pardoned for homosexual acts that were no longer considered offences under the Policing and Crime Act 2017 (homosexuality was decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967). The 2017 Act implements what is known informally as the Alan Turing law.

Oscar Wilde’s Particular Aesthetic

Chief among the literary practitioners of decorative aestheticism was Oscar Wilde, who advocated Victorian decorative individualism in speech, fiction, and essay-form. Wilde’s notion of cultural enlightenment through visual cues echoes that of Alexander von Humboldt who maintained that imagination was not the Romantic figment of scarcity and mystery but rather something anyone could begin to develop with other methods, including organic elements in pteridomania.

By changing one’s immediate dwelling quarters, one changed one’s mind as well; Wilde believed that the way forward in cosmopolitanism began with as a means eclipse the societally mundane, and that such guidance would be found not in books or classrooms, but through a lived Platonic epistemology. An aesthetic shift in the home’s Victorian decorative arts reached its highest outcome in the literal transformation of the individual into cosmopolitan, as Wilde was regarded and noted among others in his tour of America.

For Wilde, however, the inner meaning of Victorian decorative arts is fourfold: one must first reconstruct one’s inside so as to grasp what is outside in terms of both living quarters and mind, whilst hearkening back to von Humboldt on the way to Plato so as to be immersed in contemporaneous cosmopolitanism, thereby in the ideal state becoming oneself admirably aesthetical.

-

Vitrine Duffel Bag

Price range: $70.00 through $77.00 -

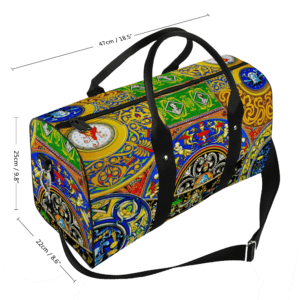

Soleil Ornate Duffel Bag

Price range: $70.00 through $77.00 -

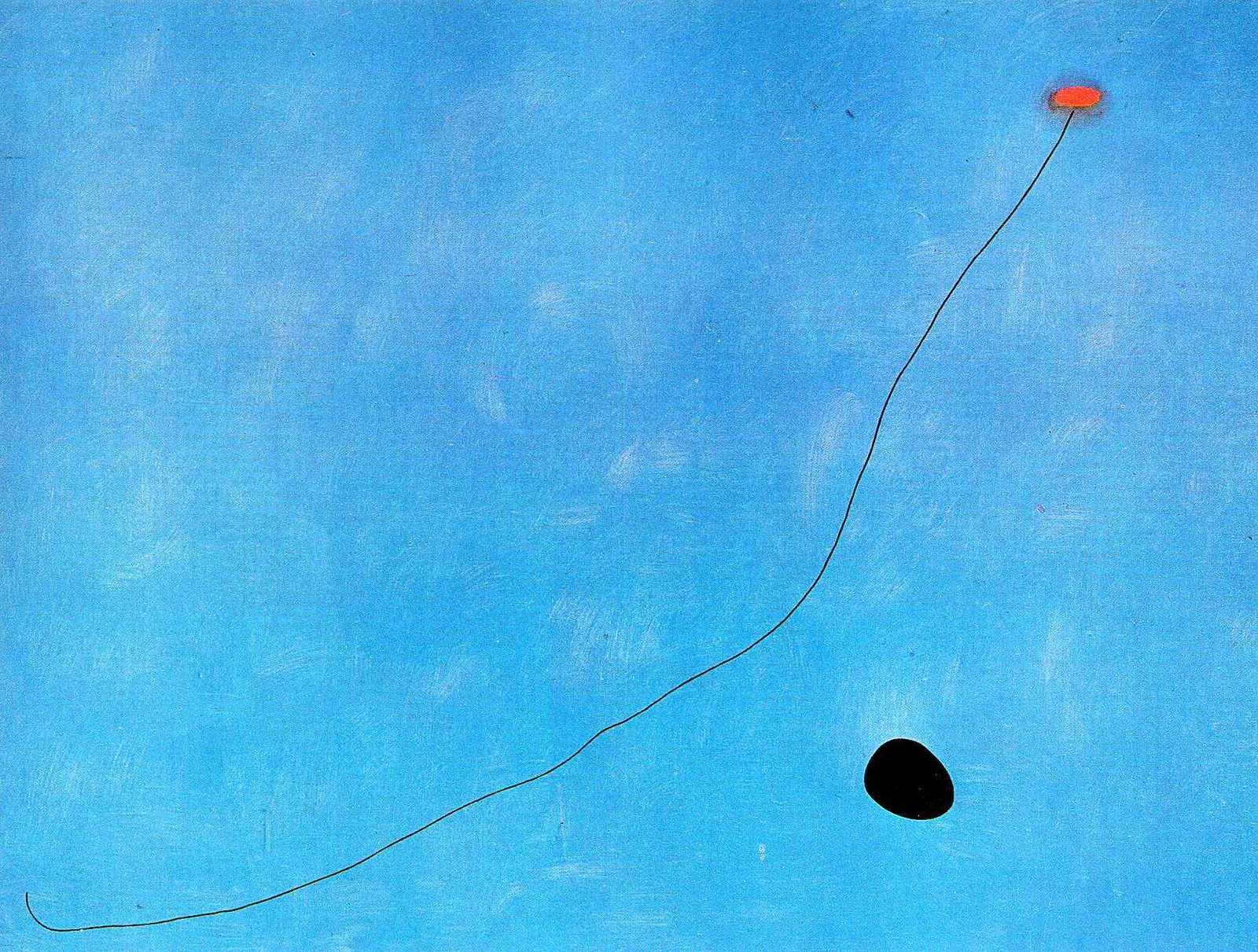

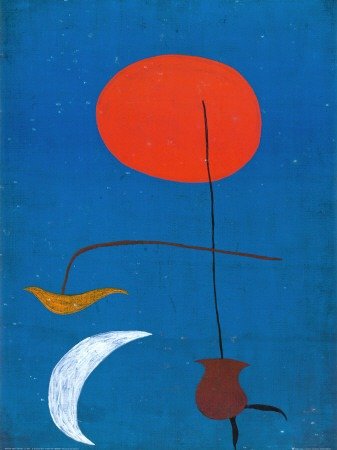

Constellation Duffel Bag

Price range: $70.00 through $78.00 -

-10%

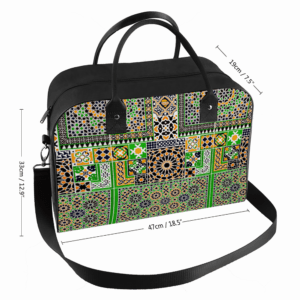

-10%Racinet “moyen âge” Large Travel Bag

Original price was: $67.00.$60.00Current price is: $60.00. -

-8%

-8%Racinet: Persia Commuter Bag Cross Body Sling

Original price was: $42.97.$39.50Current price is: $39.50. -

Egrec Hanging Toiletry Bag

$42.00 -

Racinet: Flowering Earth Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Racinet: Pompeian No. 3 Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Racinet: “Renaissance” Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Racinet: “Persian” Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Racinet: “Medieval” Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Racinet: “Persia” Tripod Lamp

$60.00 -

Racinet: Jade Flower Sherpa Blanket

Price range: $39.00 through $51.00 -

Racinet: Jade Flower (detail) Laptop Sleeve

Price range: $28.00 through $30.00 -

Racinet: Persian Women’s Racerback Dress

$36.00 -

Racinet Yoga Leggings

$41.00 -

Racinet: Japonais Bodycon Dress

$55.00 -

Racinet: Japonais Capri Leggings

$34.00 -

Racinet: Agra Reusable Shopping Bag

$28.00 -

Racinet: Japonais Gift Wrapping Paper Roll

Price range: $11.00 through $29.50