Fine Art Focus: Bauhaus: 100 years later

bauhaus

A 100-year perspectiveThe importance of the Bauhaus lies in its revolutionary approach to design, architecture, and art education that emphasized functionality, simplicity, and the integration of art with mass production, creating a lasting influence on modern design across many fields, from furniture and buildings to graphic design and beyond. Despite being a short-lived German school (1919-1933), its principles were spread worldwide, especially after its closure by the Nazis, pioneering the concept of design as a holistic, problem-solving discipline.

The school existed in three German cities—Weimar, from 1919 to 1925; Dessau, from 1925 to 1932; and Berlin, from 1932 to 1933—under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928; Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930; and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime, having been painted as a centre of communist intellectualism.[4] Internationally, former key figures of Bauhaus were successful in the United States and became known as the avant-garde for the International Style.[5] The White city of Tel Aviv, to which numerous Jewish Bauhaus architects emigrated, has the highest concentration of the Bauhaus’ international architecture in the world.

The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For example, the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it.

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 in the city of Weimar by German architect Walter Gropius (1883–1969).

Its core objective was a radical concept: to reimagine the material world to reflect the unity of all the arts. Gropius explained this vision for a union of art and design in the Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919), which described a utopian craft guild combining architecture, sculpture, and painting into a single creative expression. Gropius developed a craft-based curriculum that would turn out artisans and designers capable of creating useful and beautiful objects appropriate to this new system of living.

The Bauhaus combined elements of both fine arts and design education. The curriculum commenced with a preliminary course that immersed the students, who came from a diverse range of social and educational backgrounds, in the study of materials, color theory, and formal relationships in preparation for more specialized studies. This preliminary course was often taught by visual artists, including Paul Klee (1987.455.16), Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944), and Josef Albers (59.160), among others.

Major Bauhaus Artists

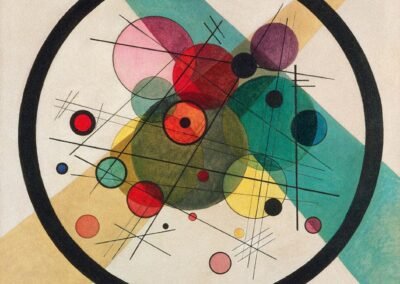

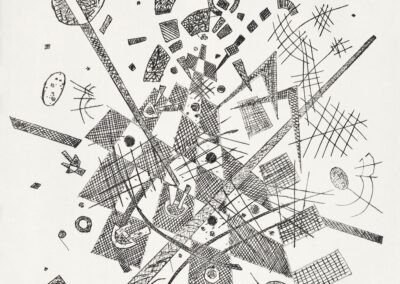

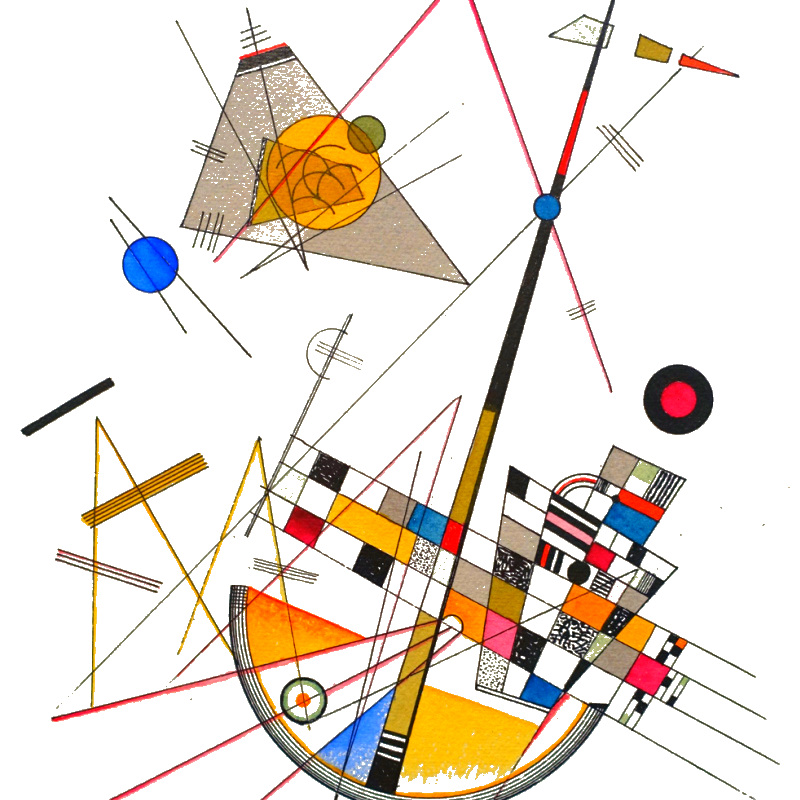

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944):

A leading figure in abstract art, he was a member of the influential Der Blaue Reiter group and taught at the Bauhaus.

Paul Klee (1879–1940):

Also a member of Der Blaue Reiter, Klee was known for his colorful, geometric abstract paintings and taught at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1932.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946):

A Hungarian artist who taught painting and photography, known for his work in kinetic sculpture and his use of light and form.

Josef Albers (1888–1976):

A German artist who was both a student and later a master at the Bauhaus, known for his work with color and geometric forms.

Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943):

A painter and sculptor who designed the Bauhaus emblem and taught painting, known for his work on the ballet “The Triadic Ballet”.

Anni Albers (1899–1994):

A significant textile artist and printmaker, she was a key figure in the women artists of the Bauhaus.

Specialization Workshops

Although Gropius’ initial aim was a unification of the arts through craft, aspects of this approach proved financially impractical. While maintaining the emphasis on craft, he repositioned the goals of the Bauhaus in 1923, stressing the importance of designing for mass production. It was at this time that the school adopted the slogan “Art into Industry.”

Architecture & Furniture Design

In 1925, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, where Gropius designed a new building to house the school. This building contained many features that later became hallmarks of modernist architecture, including steel-frame construction, a glass curtain wall, and an asymmetrical, pinwheel plan, throughout which Gropius distributed studio, classroom, and administrative space for maximum efficiency and spatial logic.

The cabinetmaking workshop was one of the most popular at the Bauhaus. Under the direction of Marcel Breuer (1983.366) from 1924 to 1928, this studio reconceived the very essence of furniture, often seeking to dematerialize conventional forms such as chairs to their minimal existence. Breuer theorized that eventually chairs would become obsolete, replaced by supportive columns or air. Inspired by the extruded steel tubes of his bicycle, he experimented with metal furniture, ultimately creating lightweight, mass-producible metal chairs. Some of these chairs were deployed in the theater of the Dessau building.

Textiles

Women and Weaving at the Bauhaus

The Bauhaus weaving workshop was one of the most inventive and commercially successful departments of the pioneering 20th-century school of art and design. Notably, most of the artists involved were women.

These women were “exploring textiles’ potential, both as works of art and as utilitarian fabrics,” said Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs and curator of The Bauhaus and Harvard at the Harvard Art Museums.

Collaboration and innovation were paramount in the workshop: artists pursued new designs suitable for industrial production and experimented with novel materials and techniques.

Source —Harvard Art Museums

The textile workshop, especially under the direction of designer and weaver Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983), created abstract textiles suitable for use in Bauhaus environments.

Students studied color theory and design as well as the technical aspects of weaving. Stölzl encouraged experimentation with unorthodox materials, including cellophane, fiberglass, and metal. Fabrics from the weaving workshop were commercially successful, providing vital and much needed funds to the Bauhaus. The studio’s textiles, along with architectural wall painting, adorned the interiors of Bauhaus buildings, providing polychromatic yet abstract visual interest to these somewhat severe spaces.

While the weaving studio was primarily comprised of women, this was in part due to the fact that they were discouraged from participating in other areas. The workshop trained a number of prominent textile artists, including Anni Albers (1899–1994), who continued to create and write about modernist textiles throughout her life.

Metal & Industrial Design

Metalworking was another popular workshop at the Bauhaus and, along with the cabinetmaking studio, was the most successful in developing design prototypes for mass production. In this studio, designers such as Marianne Brandt (2000.63a–c), Wilhelm Wagenfeld (1986.412.1–16), and Christian Dell (1893–1974) created beautiful, modern items such as lighting fixtures and tableware. Occasionally, these objects were used in the Bauhaus campus itself; light fixtures designed in the metalwork shop illuminated the Bauhaus building and some faculty housing.

Brandt was the first woman to attend the metalworking studio, and replaced László Moholy-Nagy (1987.1100.158) as studio director in 1928. Many of her designs became iconic expressions of the Bauhaus aesthetic. Her sculptural and geometric silver and ebony teapot (2000.63a–c), while never mass-produced, reflects both the influence of her mentor, Moholy-Nagy, and the Bauhaus emphasis on industrial forms. It was designed with careful attention to functionality and ease of use, from the nondrip spout to the heat-resistant ebony handle.

Typography

The typography workshop, while not initially a priority of the Bauhaus, became increasingly important under figures like Moholy-Nagy and the graphic designer Herbert Bayer (2001.392). At the Bauhaus, typography was conceived as both an empirical means of communication and an artistic expression, with visual clarity stressed above all. Concurrently, typography became increasingly connected to corporate identity and advertising. The promotional materials prepared for the Bauhaus at the workshop, with their use of sans serif typefaces and the incorporation of photography as a key graphic element, served as visual symbols of the avant-garde institution.

Cessation, Nationalism and the new beginning

Gropius stepped down as director of the Bauhaus in 1928, succeeded by the architect Hannes Meyer (1889–1954). Meyer maintained the emphasis on mass-producible design and eliminated parts of the curriculum he felt were overly formalist in nature. Additionally, he stressed the social function of architecture and design, favoring concern for the public good rather than private luxury. Advertising and photography continued to gain prominence under his leadership.

Under pressure from an increasingly right-wing municipal government, Meyer resigned as director of the Bauhaus in 1930. He was replaced by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1980.351). Mies once again reconfigured the curriculum, with an increased emphasis on architecture. Lilly Reich (1885–1947), who collaborated with Mies on a number of his private commissions, assumed control of the new interior design department.

Other departments included weaving, photography, the fine arts, and building. The increasingly unstable political situation in Germany, combined with the perilous financial condition of the Bauhaus, caused Mies to relocate the school to Berlin in 1930, where it operated on a reduced scale. He ultimately shuttered the Bauhaus in 1933.

During the turbulent and often dangerous years of World War II, many of the key figures of the Bauhaus emigrated to the United States, where their work and their teaching philosophies influenced generations of young architects and designers.

Breuer and Gropius taught at Harvard. Josef and Anni Albers taught at Black Mountain College, and later Josef taught at Yale.

Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937.

Mies van der Rohe designed the campus and taught at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

It remains to this day, standing as a distinguished monument to the power of art.

Showing all 35 resultsSorted by latest

-

Paul Klee: Color Chart Haori Kimono

$68.00 -

Klee: Polyphonic Architecture Custom Shower Curtain

$41.00 -

Klee’s “Qu 1” Color Chart Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Klee’s “Untitled” Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Klee’s “Late Evening” Area Rug

Price range: $40.00 through $120.00 -

Paul Klee: “Qu1” Tripod Lamp

$60.00 -

Paul Klee: “Late Evening Looking Out of the Woods ” Tripod Lamp

$60.00 -

Paul Klee Color Chart Glass Cutting Board

Price range: $22.00 through $30.00 -

Paul Klee: Color Chart Shoulder Handbag

$49.00 -

Paul Klee: “Old City” (1928) Fleece Sherpa Blanket

Price range: $50.00 through $65.00 -

Paul Klee Duet Tufted Floor Pillow, Square

Price range: $51.00 through $75.00 -

Klee’s Color Chart Luggage Cover

Price range: $30.00 through $40.00 -

Paul Klee: “The Firmanent Above the Temple” Microfiber Pillow Sham

Price range: $32.00 through $35.00 -

Miro Dress Vest

$33.00 -

Paul Klee Area Rug

Price range: $37.00 through $110.00 -

Paul Klee: Rhythms Waterproof Travel Bag

$110.00 -

Paul Klee: Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black (1925) Duffel Bag

$69.00 -

Kandinsky: Four Parts (1932) Cosmetic Case

$34.00 -

Kandinsky: Delicate Tensions (1923) Leather Handbag

$66.00 -

Joan Miró: Constellation Utility Cross Body Bag

$31.00 -

Kandinsky: Squares with Concentric Circles (1913) Box Tee

Price range: $34.50 through $37.50 -

Kandinsky: Color Study (1913) Utility Crossbody Bag

$30.50 -

Senecio Klee Shopping Bag

$24.00 -

Paul Klee: Clarification Reusable Shopping Bag

$24.00 -

Paul Klee: First House in a Settlement (1926) Cross-body Bag

$33.00 -

Paul Klee & Robert Delauney: Fish and Circles Throw Pillow

Price range: $28.00 through $55.00 -

Miro Design Small Shoulder Bag

$35.00 -

Joan Miró: The Gold of the Azure (L’Or de l’azur) Utility Crossbody Bag

$31.00 -

Joan Miró: Birds and Insects, 1938 Utility Crossbody Bag

$31.00 -

Joan Miró: Peinture, 1933 Utility Crossbody Bag

$31.00 -

Joan Miró: Peinture (Le Soleil), 1927 Utility Crossbody Bag

$31.00 -

L’Or de l’azur Oversized Weekender Bag

$48.00 -

Klee-Inspired Oversized Weekender Bag

$48.00 -

Paul Klee-Inspired Recycled High-waisted Bikini

Price range: $46.00 through $50.00 -

Paul Klee: Lovers (1920) Utility Crossbody Bag

$31.00