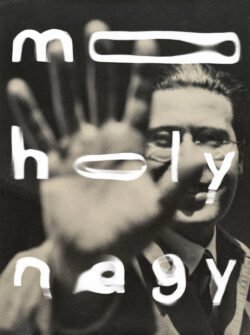

László Moholy-Nagy

(1895–1946)

Writer, theorist, teacher, painter, philosopher, photographer, sculptor and curator, László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) was one of 20th-century art’s great innovators. ‘Openness to exploration, to experimentation, is very much part of his aesthetic’, affirms Carol Eliel, who curated Moholy-Nagy: Future Present at LACMA, the first American retrospective of the artist since 1969.

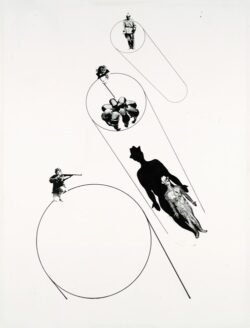

Moholy-Nagy became active in the Berlin scene, enthusiastically absorbing Europe’s new art movements. ‘He did a number of drawings and paintings in Hungary which were really influenced by Cubism, before Dada seeped into his consciousness,’ the curator explains. The Dada aesthetic of experimentation and radicalism particularly appealed to Moholy-Nagy, as did Constructivist abstraction.

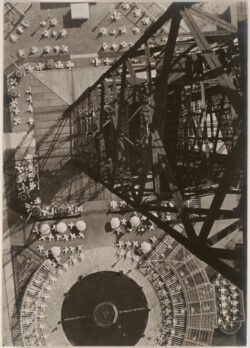

Moholy-Nagy believed that photography was ‘the essential visual vocabulary of the day’, and that a lack of familiarity with photography made one, on an artistic level, ‘illiterate’.

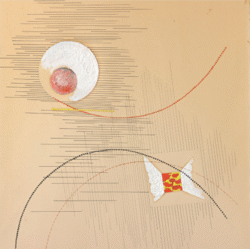

‘The notion of experimentation was critical to his practice,’ continues Eliel, describing how he went on to invent the photogram — a photograph made without a camera. To create a photogram, Moholy-Nagy laid objects on light-sensitive paper and exposed them to light, with a longer exposure creating a brighter image.

Moholy-Nagy’s artistic reputation grew, bringing with it a career-defining opportunity at the Bauhaus in 1923. ‘Walter Gropius, the head of the Bauhaus at the time, invited him to teach there. Moholy-Nagy was interested in the connections between art, industry and technology, and Gropius wanted to strengthen that aspect of training,’ Eliel explains.

Moholy-Nagy taught the foundation course as well as in the metal workshop, but his role went considerably beyond that of teacher, says the curator. ‘Moholy-Nagy was very influential in creating — with others — the graphic look of the Bauhaus. He became a pillar of Bauhaus aesthetics.’

Moholy-Nagy died in 1946, at the age of 51. Had he lived to see the computer age, believes Eliel, he would have been thrilled. ‘He would be all over digital media, computer art and the internet,’ she says. ‘Those are exactly the kind of intellectual ideas that would have completely fascinated and inspired him — the notion of the endlessly reproducible image that can go out into the world on a multitude of platforms is something he would have loved.’

—Source: Christie’s